What is inside of a seed? A new plant? Maybe a new tree? Will your students believe you? Seeds are relatively small (with the exception of coconuts) but have the potential to grow into productive plants. How can such a small package contain such potential? This lesson contains a simple yet enlightening activity you can do with your students to help them understand seeds and seed development.

Seeds have many uses. Some seeds can be eaten, like sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, peanuts, and coconuts. We can extract oil from some seeds and grind other seeds to make flour. Seeds are used to grow fruits and vegetables to eat, as well as flowers, trees, and other plants that we enjoy in our surroundings. Seeds are all around us.

Most seeds can be stored for a long time and kept in a dormant or nongrowing state. Each seed contains all of the genetic information for the plant it can grow into. Once a seed is placed in the proper environment, it will germinate or begin to grow. Proper temperature and moisture are critical for a seed to germinate.

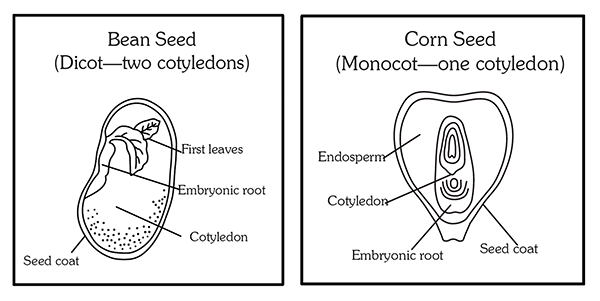

Flowering plants and their seeds can be classified into two groups: monocots and dicots. The number of cotyledons (seed leaves) distinguishes whether a seed is a monocot or dicot. Monocots have one cotyledon and dicots have two. In most dicot seeds, the cotyledons store the food that the seed will use to grow until it gets its first true leaves and begins to make its own food. In many monocot seeds, the food supply for the embryo is stored separately in tissue called the endosperm. The cotyledon absorbs and transmits the food from the endosperm to the embryo.

Generally, when monocots germinate and begin to grow, a single leaf will emerge from the soil. Monocot plants are characterized by having parallel veins and thin, strap-like leaves. Examples of monocot plants include grass, daylilies, corn, and coconuts.

Dicots generally emerge from the soil with more than one leaf. Many dicots’ cotyledons emerge from the soil, turn green, and perform photosynthesis. These types of seedlings are the easiest to recognize as dicots because they have two leaves (the cotyledons) that look different from the leaves of the mature plant. Dicot plants have veins that form a net-like pattern across the leaves. Most flowers and fruit and vegetable plants are classified as dicots.

Botanists classify or categorize plants to make it easier to study and understand them. There are hundreds of thousands of different plant species, so it would be very difficult to study them all. Breaking them up into smaller groups with similar characteristics helps organize the way we study and think about plants. Not all plants are classified as monocots or dicots—this is a classification used only for the group that botanists call flowering plants. Older plants that developed earlier in the history of Earth are classified differently, although they have some similar parts. Ferns and pine trees are examples of plants that are not flowering plants and therefore are neither monocots nor dicots. It is interesting to compare pine nuts to monocot and dicot seeds because they have similar parts, but pine nuts have more than two cotyledons (the cotyledons of the pine nut look like the “leaves” of the embryo).

Three parts of a seed are discussed in this lesson: the seed coat, the food supply, and the embryo. Almost all seeds have these three parts whether they are monocots, dicots, or neither (e.g., conifers like pine and spruce trees). The seed coat is the outer covering, which provides protection for the seed. The seed coat can be thin, like on a bean seed, or thick and hard, like on a pine nut or coconut. The food supply is a large part of the seed that contains the nutrients and energy that the embryo will use to grow. In dicots, the cotyledons generally contain the food supply. In other seeds, the food supply is separate from the cotyledons and is commonly called the endosperm. The purpose of the food supply is to nourish the embryo. The embryo is the “baby” plant, or the portion of the seed that will develop into the seedling’s leaves and roots. Technically, the food supply is part of the embryo, but while the embryo grows, the food supply shrinks.