Earthworms are found everywhere on the earth’s surface, except the north and south poles, where it is too cold. They can be so tiny you can’t see them without a microscope, or they can be several feet long. There are thousands of different species of earthworms, and they have many common names, such as orchard worm, rain worm, angleworm, red wiggler, night crawler, and field worm.

The earthworm has no head, no eyes, no teeth, and no antennae. Its body is made up of many ring-like segments, each of which has bristles that the worm can extend and retract to help it move through the soil. Earthworms don’t have any lungs either. They breathe through their skin, which has to stay moist so oxygen can pass through. Worms can live for a long time in water, as long as the water has oxygen in it, but they will die if their skin dries out. They can also die if they’re exposed to ultraviolet rays from the sun for too long. Earthworms have both male and female reproductive organs, but their eggs still need to be fertilized by another worm. They lay capsules full of fertilized eggs called cocoons. Depending on the species, their cocoons may contain one to several baby worms. Baby worms look like tiny threads when they first emerge.

The worm is the gardener’s best friend. Night and day, worms burrow through acres of ground, swallowing soil as they go. Inside the soil are tiny bits of plants and animals that they grind up as they eat. Worms can taste what they eat and prefer some foods over others. In experiments worms have demonstrated a preference for carrot leaves over celery and celery over cabbage. While they’re eating, a lot of soil passes through the guts of earthworms. Through the process of digestion, nutrients that were locked up in the soil and unavailable to plants or other organisms are released in worms’ waste, which gardeners call castings.

Worm castings are lumps and bumps of soil that come out the back end of a worm. Castings are rich in nutrients such as nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus that help plants grow. The average earthworm will produce its own weight in castings every 24 hours. One earthworm can digest several tons of soil in a year. Not only do castings add nutrients to the soil, but they also improve the soil’s ability to hold water, another bonus for plants. As worms burrow and tunnel, they aerate the soil, providing a looser structure and openings for roots to grow. Their tunnels provide channels for water to enter the soil and improve drainage. Worms are like small rototillers and bags of fertilizer in a very small, and somewhat slimy, package.

Worms are also like nature’s recyclers. We are part of a living and dying world. Plants and animals are born, grow old, and die. Other plants and animals take their places. As each living thing dies, it decays and returns to the soil. One plant’s death may make it possible for new plants to grow where they could not grow before. Worms help speed this process by eating living and dead plant material, digesting it, and depositing it back in the soil as nutrient- rich castings. The relationships between plants, soil organisms like worms, and their environment is known as ecology.

Leaves that fall to the ground in the autumn are a very important part of the forest ecology, or nutrient cycle. The leaves lie on top of others that fell in previous years. This is called forest litter, and it is made up of organic matter. Winter rains and snows keep the leaves wet so decomposers like worms can do their work. There are many different organisms living under the piles of leaves in the dirt that work as decomposers. Some of them are so tiny you can’t see them without a microscope. You are seeing thousands of decomposers all massed together when you see fungi or mold. Decomposers release nutrients from the dead leaves into the soil. In the spring, new plants use those nutrients to grow new leaves.

The process of leaf decomposition on the forest floor is similar to the process of decomposition that happens in a gardener’s compost. Decomposers make healthy soils in natural ecosystems and in the gardens and farms where our food is grown.

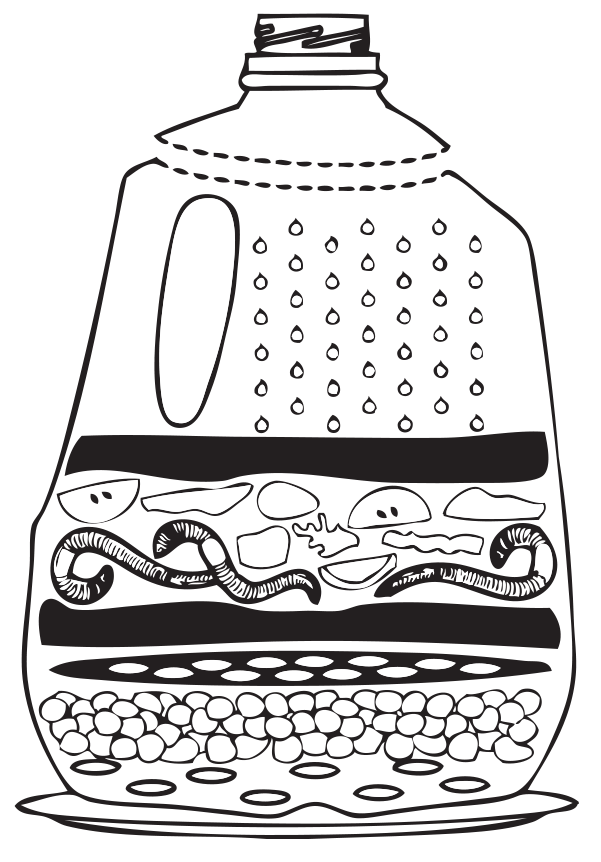

Poke holes in a plastic lid or plate and place over the gravel.

Poke holes in a plastic lid or plate and place over the gravel.