|

From Wool to Wheel uses the College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework's Inquiry Arc as a blueprint to lead students through an investigation of the importance of wool in Colonial America. The Inquiry Arc consists of four dimensions of informed inquiry in social studies:

- Developing questions and planning inquiries;

- Applying disciplinary concepts and tools;

- Evaluating sources and using evidence;

- Communicating conclusions and taking informed action.

The four dimensions of the C3 Framework center on the use of questions to spark curiosity, guide instruction, deepen investigations, acquire rigorous content, and apply knowledge and ideas in real world settings to become active and engaged citizens in the 21st century.2 For more information about the C3 Framework, visit socialstudies.org.

C3 Table- Wool to Wheel |

Wool in Colonial America

Wool played an important role in Colonial America. Before the Revolutionary War, most of the finest textiles and fashionable styles were imported from Great Britain. Many colonists wanted to produce their own clothing and textile goods. Wool and linen were the most common materials used. Homespun clothes, clothes that were produced by the colonists, reduced the amount of clothing that had to be bought from England.

In 1699, under the rule of King William III, the British Parliament issued the Wool Act which prohibited American colonists from exporting wool or wool products outside of the colony in which it was produced. The king banned the export of sheep to the American colonies in an effort to protect England’s wool industry. Wool could only be imported into the colonies by Great Britain. The Wool Act was one of a series of taxes that divided Great Britain and its colonies in America.

The colonists began protesting the Wool Act by refusing to purchase or wear English textiles. Many colonists refused to purchase English goods. It became a patriotic act to wear American homespun clothing. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin are notable figures who wore homespun clothing as a patriotic statement of their devotion to American independence and freedom. In the American colonies, spinning and weaving wool became a necessity and a patriotic duty.

In Colonial times, the process of making wool cloth began with shearing sheep in early spring with hand clippers. The wool was cleaned through a process called scouring in which the wool underwent a series of baths before it was laid out to dry.

Wool grease is produced as part of the wool’s growth and helps protect the sheep’s wool and skin from the environment. Scouring removes this grease from the wool. The grease can be captured from the scouring water. When it is refined, this grease is known as lanolin. Lanolin can be used in moisturizers, cosmetics, medicine, and industrial applications.

In preparation for spinning, wool must be carded. The colonists used hand carders to comb the wool, remove debris, and untangle the fibers, aligning them parallel with each other. Colonists used dye formulas that included insects, roots, flowers, nuts, seeds, tree bark, leaves, or berries. Because of the toxic chemistry, many of these colonial dyes have been deemed unsafe in our era. The dyeing process involved soaking wool in kettles of dye over fires for several hours.

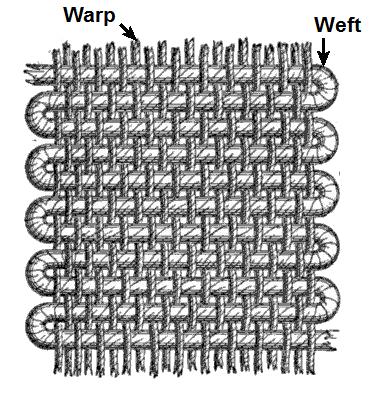

Wool was spun into thread or yarn by tightly twisting the fibers using a spinning wheel. Weavers turned the wool thread into cloth using looms. Wool was also felted, a process of matting fibers together, to make products such as hats and slippers.

Ask the students, "What happens when you grow out of your clothes?" After several students answer, explain that they are going to hear a story about a Colonial girl who grew out of her clothes.

Ask the students, "What happens when you grow out of your clothes?" After several students answer, explain that they are going to hear a story about a Colonial girl who grew out of her clothes.