New Mexico's state question, “Red or Green?” is the perfect example of how New Mexicans have survived together, maintained their heritage to create a unique multi-cultural legacy. The traditional cuisine of the Southwest is a literal expression of that blending of agricultural products from all parts of the world. The enchilada is a product of those who were here and those who came after. It is made up of corn tortillas (American origin), beef or chicken (European origin), cheese (European origin) and green or red chile (Meso-American brought by Spanish settlers). This project seeks to discover the movement of several agricultural products to New Mexico from Europe and Mesoamerica with the Spanish explorers and settlers and the subsequent assimilation into the “Whole Enchilada.”

Columbian Exchange

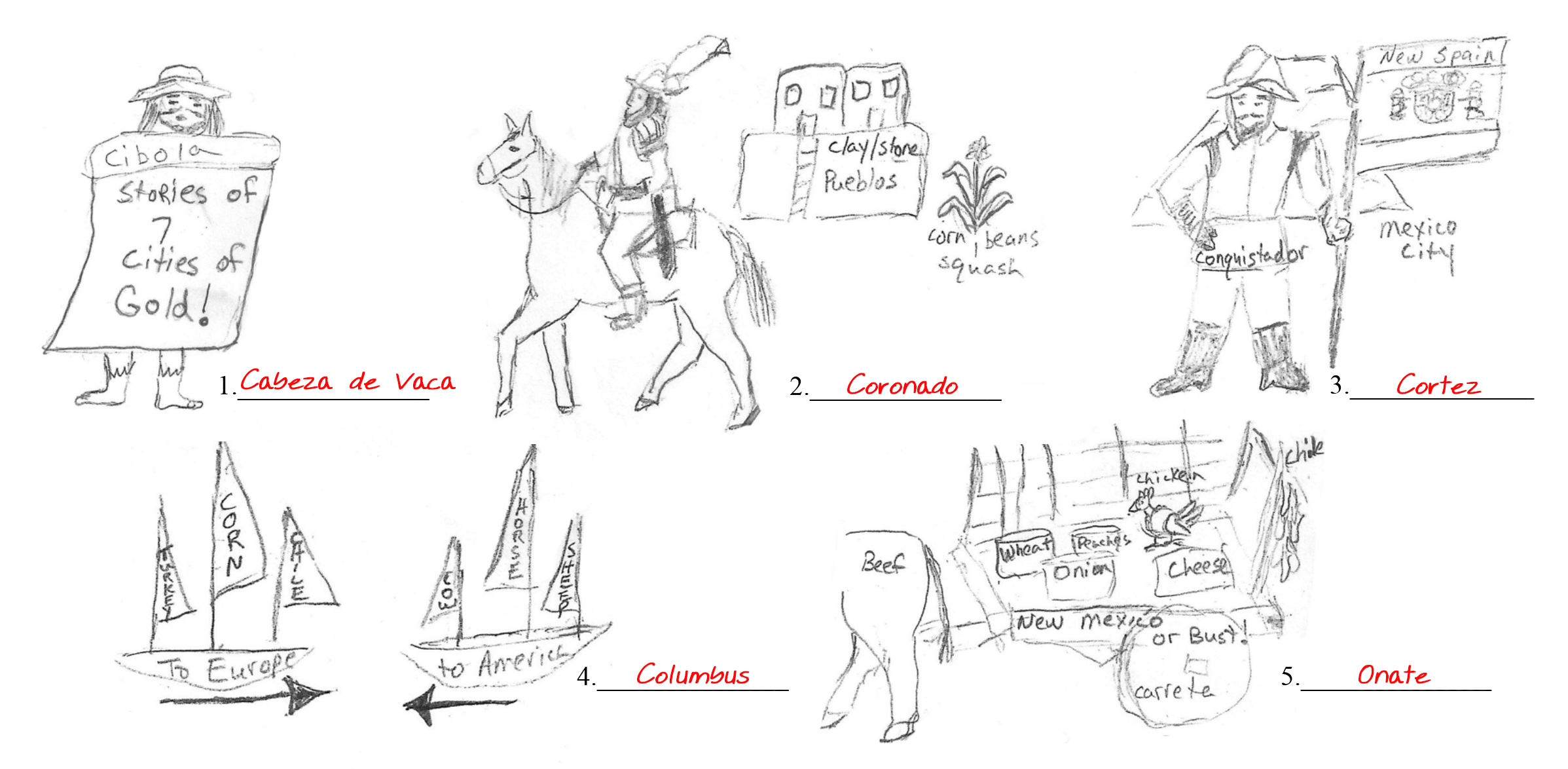

Beginning with Christopher Columbus's expeditions and the conquest of the Americas, agriculture changed the world's food supply and civilization like no other event in history. The New World gave things like chocolate, peanuts, corn, pumpkins, turkey, tobacco, chile and potatoes to Europe, while the Old World brought cattle, sheep, goats, horses, stone fruits, donkeys and wheat to the Americas. From the West Indies, exploration moved west toward Central America. This lesson focuses primarily on the explorers of the American Southwest and only prefaces the Columbian Exchange. For a more in-depth lesson on the Columbian Exchange consider teaching The Columbian Exchange of Old and Ne World Foods as a preface to this lesson.

Early Spanish Explorers

In search for more slaves for the sugar cane plantations of the West Indies, Hernando Cortez discovered the vast riches of the Aztec Empire at Tenochtitlan (today’s Mexico City). In 1521 with the conquest of the Aztecs and the establishment of New Spain, Cortez and the Spanish introduced European livestock and plants to New Spain (Mexico). The Spanish adopted the chile pepper and corn into their cuisine and crops. Farms, ranches, mines and villas were developed and lands were plowed, planted and built on steadily moving toward the North.

It wasn’t just land that the Spanish wanted, the stories of more gold pushed them as well. With the fabulous treasures they acquired from the Mexica, a fever was fueled for more riches fabled to be far north of the Aztec empire in a land called "Quivira". Alvar Cabeza de Vaca, a shipwreck survivor who wandered around the Southwest from 1528-1536, spread more tales about the Seven Cities of Gold. Ill-fated expeditions by Fray Marcos de Niza (1539) and a 3 year trek by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado yielded geographical knowledge of the Southwest but no riches. He explored the land of the Pueblos where he found villages with fields of corn, beans, and squash. Their only domesticated livestock were turkeys and small dogs. The natives saw horses, muskets and Spanish soldiers for the first time.

40 years would pass before the legends of a "New Mexico" would reappear with mines in New Spain needing more workers and an expanding population of Spanish settlers wanting land and riches. Don Juan de Onate, the son and son-in-law of conquistadores/settlers of Zacatecas, was commissioned by Spain's King Philip to establish the first permanent colonies/farms in New Mexico. Between 1598 and 1608, San Juan de los Caballeros, then San Gabriel near present day Ohkay Owingeh (formerly named San Juan Pueblo) were founded and estancias developed. The Spanish utilized irrigation methods developed by the Pueblo with acequia systems that are used today, and the Pueblos were introduced to many new crops and domestic animals, especially the horse and sheep. Slave labor, known as the encomienda system, was used to build churches, develop estancias and haciendas, and force the natives to adopt Spanish culture.

Even though these first efforts failed due to disease, drought, conflicts and deplorable treatment of the natives, agriculture and technology were forever changed. New cuisine that incorporated corn, beans, squash, beef, chicken and chile were now possible. Dairy products including cheese and fresh milk (usually from goats) were available, and the famous New Mexico enchilada had all the ingredients to be compiled into a new dish enjoyed by settlers and natives. Horses, mules, donkeys, oxen and the wheeled cart (carreta) changed transportation and farming methods. Trade fairs selling commodities further disseminated new products and technologies.

The Enchilada: A Symbol of New Mexico's Agricultural Legacy

Today, our enchilada is an adopted part of the symbols of the American Southwest as well as its components being important contributors to the economy. As we layer corn tortillas, beef, cheese and chile sauce, we can visualize the farms, ranches, dairies and cheese factories that make it possible. Beef cattle are New Mexico’s number one crop raised throughout the state. Dairy products rank number two with a couple of the largest cheese factories in the US and around 320,000 cows in 2012. Chile is a main crop of the lower Rio Grande Valley in Hatch and Las Cruces, providing 37% of the nation’s supply. Corn fits in as eighth for cash receipts, and is mainly used as feed grain.3

Middle school students are ready to learn how to prepare simple main dishes. The enchilada is nutritious, containing vegetables, meat, grain and dairy; it’s traditional, and it’s tasty!