About 10,000 years ago people began to figure out how to grow grains during the summer, store them for winter food, and use the leftover grains to plant the next year—this was the beginning of agriculture. Around the world, grain cultivation was closely linked to the growth of civilizations. Grains like corn, rice, and wheat produce seeds packed with energy and nutrition that are easy to store and transport. All of these grain crops originated as wild grasses. Over many years, people saved and replanted seed from the grasses with the most beneficial traits. Through hundreds of years of selection, people domesticated the wild grasses, turning them into the ancestors of the grain crops we know today.

Evidence suggests that wheat was first domesticated somewhere in the Middle East approximately 10,000 years ago. Many anthropologists speculate that primitive people probably chewed the wheat kernels before they learned to pound them into flour, which could be mixed with water to make porridge. From its center of origin in the Middle East, wheat spread throughout Europe and Asia.

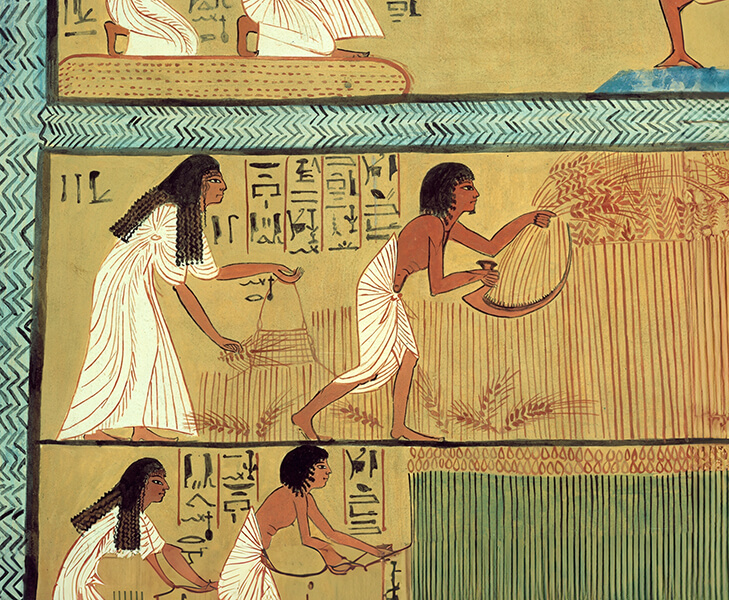

The ancient Egyptians were not the first to cultivate wheat, but certainly wheat was one of their staple foods, and they were the first to discover how to make yeast-leavened bread. They fermented flour mixtures by using wild yeasts present in the air. Even though the Egyptians made leavened bread, they did not understand that it was the yeast in the air that caused bread to rise. It was not until the 1800s that yeast was identified as an organism that converts sugars into alcohol, producing a leavening gas (carbon dioxide) in the process. Because wheat is the only grain with sufficient gluten content to make leavened bread, wheat quickly became favored over other grains grown at the time, such as oats, millet, rice, and barley. The workers who built the pyramids in Egypt were paid in bread. Bread for the rich was made from wheat flour, bread for those who weren’t wealthy was made from barley, and bread for the poor was made from sorghum.

Loaves of bread were commonly included in Egyptian burials as food for the journey to the afterlife. Model granaries containing wheat and other grains were also included in tombs. Many years later, in the mid-1800s, British archeologists exploring Egyptian tombs found these granaries and attempted to grow the grains. This is where the myth of mummy wheat began. Some claimed that the grains grew and produced more seed, which they then offered for sale. However, scientists have shown that it would be impossible for wheat seeds to grow after hundreds of years in a tomb.2

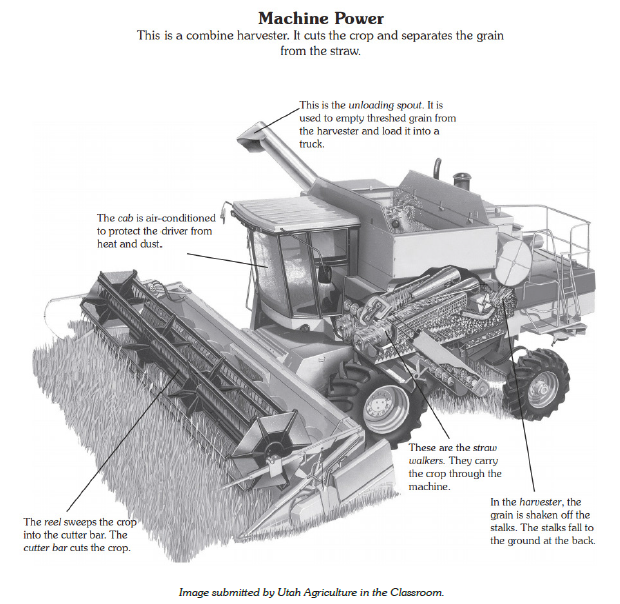

Wheat didn’t arrive in the United States until after the early voyages of Christopher Columbus. Here, the invention of the mechanical reaper by Cyrus McCormick in 1831 made it possible to harvest wheat much more efficiently. By hand, farmers could cut only two acres of wheat per day. With Cyrus McCormick’s invention of the mechanical reaper, farmers could cut eight acres a day. Many following improvements in harvesting technology make it possible for today’s farmers to harvest 150–200 acres of wheat in a single day.3

Today, wheat is an important staple food around the world, providing the flour needed to make bread, pasta, bagels, pizza crust, cakes, cookies, pretzels, and much more. Modern wheat production and processing is very different and much more efficient than that practiced by the ancient Egyptians. In ancient Egypt, wheat fields were cultivated entirely with human and animal power. The wheat was harvested with a hand tool called a sickle and threshed by using oxen to tread on the wheat. The seeds were then winnowed by hand and ground into flour by hand using large stones.4 Today, specialized machines do all of this processing. Giant combines harvest, thresh, and winnow the wheat, which is then trucked to a mill where it is further cleaned, analyzed, ground, sifted, and blended into different flours.

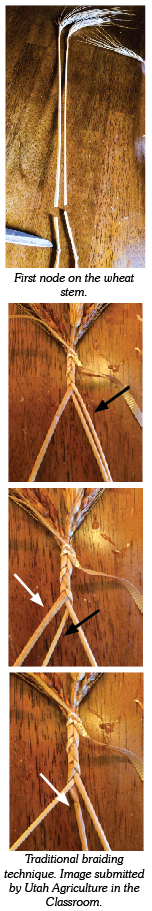

In addition to using wheat seeds for food, the stems can be woven into artful decorations and useful household items like baskets. The art of weaving with wheat stems (straw) is practically as old as wheat itself and has played an important role in harvest rituals for many different cultures. The ancient Egyptians believed in a spirit that lived in the wheat. By saving the last wheat stems and weaving them into an ornament, the farmer provided a home for the spirit until the next growing season. Similar beliefs and rituals were found in ancient Greece and Rome. The Roman goddess of the fields was Ceres, whose name is the origin of the word cereal. Red poppies, believed to bring luck, were Ceres’s favorite flowers. This may have led to the tradition of tying decorative red ribbons to wheat weavings.

In Britain, wheat weavings were known as corn dollies. Here, the word corn was used as a generic term for any type of grain, and dolly probably originated as a corruption of the word idol. Traditionally, corn dollies were made using the last stems of harvested grain. Wheat was most common, but oats, rye, barley, and corn were also used. The woven ornaments with the heads of grain still on the stem were hung on inside walls where they made it safely through the winter. These sacred grains were then planted the next season to ensure the fertility of the entire crop.5