Climate Change

The earth is heated by the sun, and when the sun’s heat reaches earth, greenhouse gases (GHG)—such as carbon dioxide—trap the heat and keep it from returning back into outer space. This process is called the greenhouse effect. Trapping some heat is a good thing because it keeps the planet warm enough for living organisms to inhabit the earth. However, humans are releasing additional carbon dioxide into the atmosphere which traps higher levels of heat causing the Earth’s temperature to rise. The increase in temperature affects our climate, resulting in climate change. Increasing temperatures and global warming affect our weather with more powerful storms, more flooding, heatwaves, and droughts. However, humans can reduce their carbon footprint by utilizing solar and wind power, driving fuel efficient cars, and reducing electricity use. Agriculture—specifically farming equipment, livestock, and soil—is another sector that contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the United States. Farmers and ranchers continue to look for ways to mitigate carbon emissions while still producing food and fiber.

Carbon in the Earth & Atmosphere

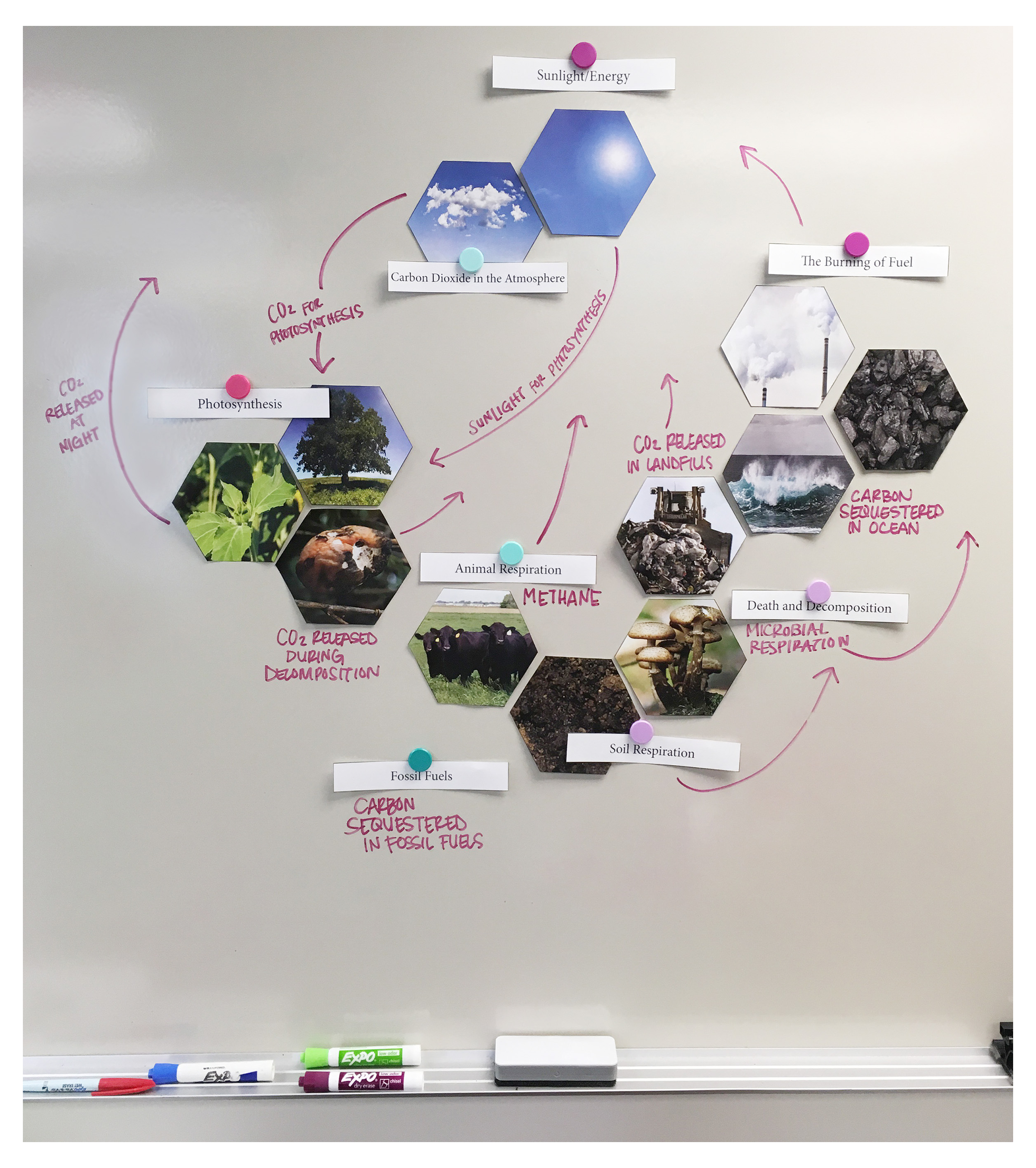

Carbon found in the earth and atmosphere is constant, and like all chemical elements, it is neither created nor destroyed. Carbon appears in various forms—either in its purest state (diamonds or graphite) or as a carbon compound. Carbon compounds form the basis of all life on earth and are found in the tissues of all plants and animals. One of the most common carbon compounds is carbon dioxide (CO2). During photosynthesis, plants use the carbon from carbon dioxide to create sugars. Animals then eat plants to receive the energy they need, and when the bodies of animals decompose, they release carbon back into the atmosphere.

Fossil fuels—coal, natural gas, and petroleum—are created from the bodies of plants and animals that died millions of years ago. Fossil fuels contain carbon because they come from once-living organisms. Humans worldwide depend on fossil fuels for many energy needs. The burning of fossil fuels also releases CO2 back into the atmosphere.

The movement of carbon through various forms and places is called the carbon cycle. When carbon is in the atmosphere, it combines with oxygen to become carbon dioxide—a greenhouse gas. The more carbon dioxide and greenhouse gases there are in the air, the warmer the temperatures on land and in the oceans.3

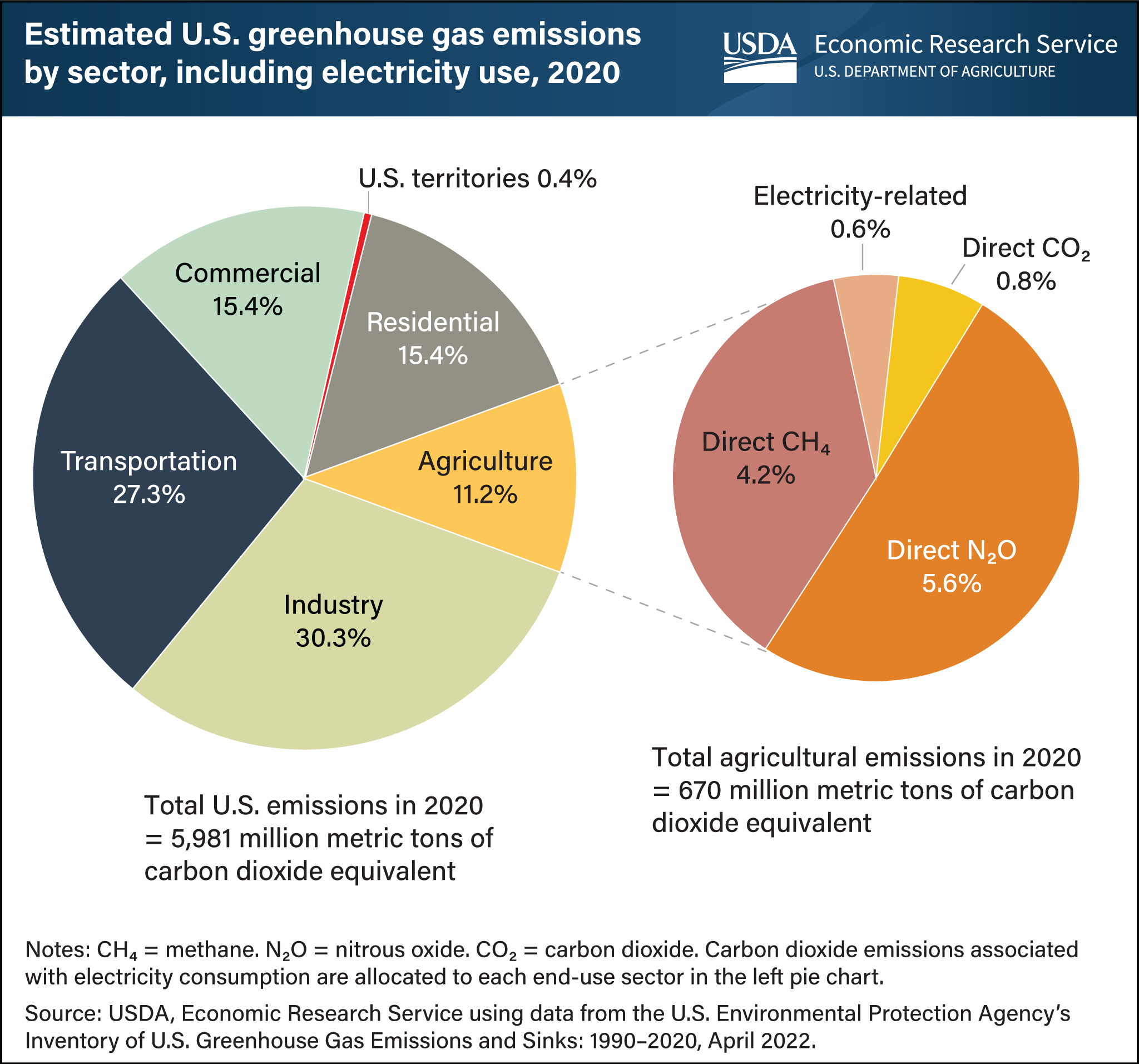

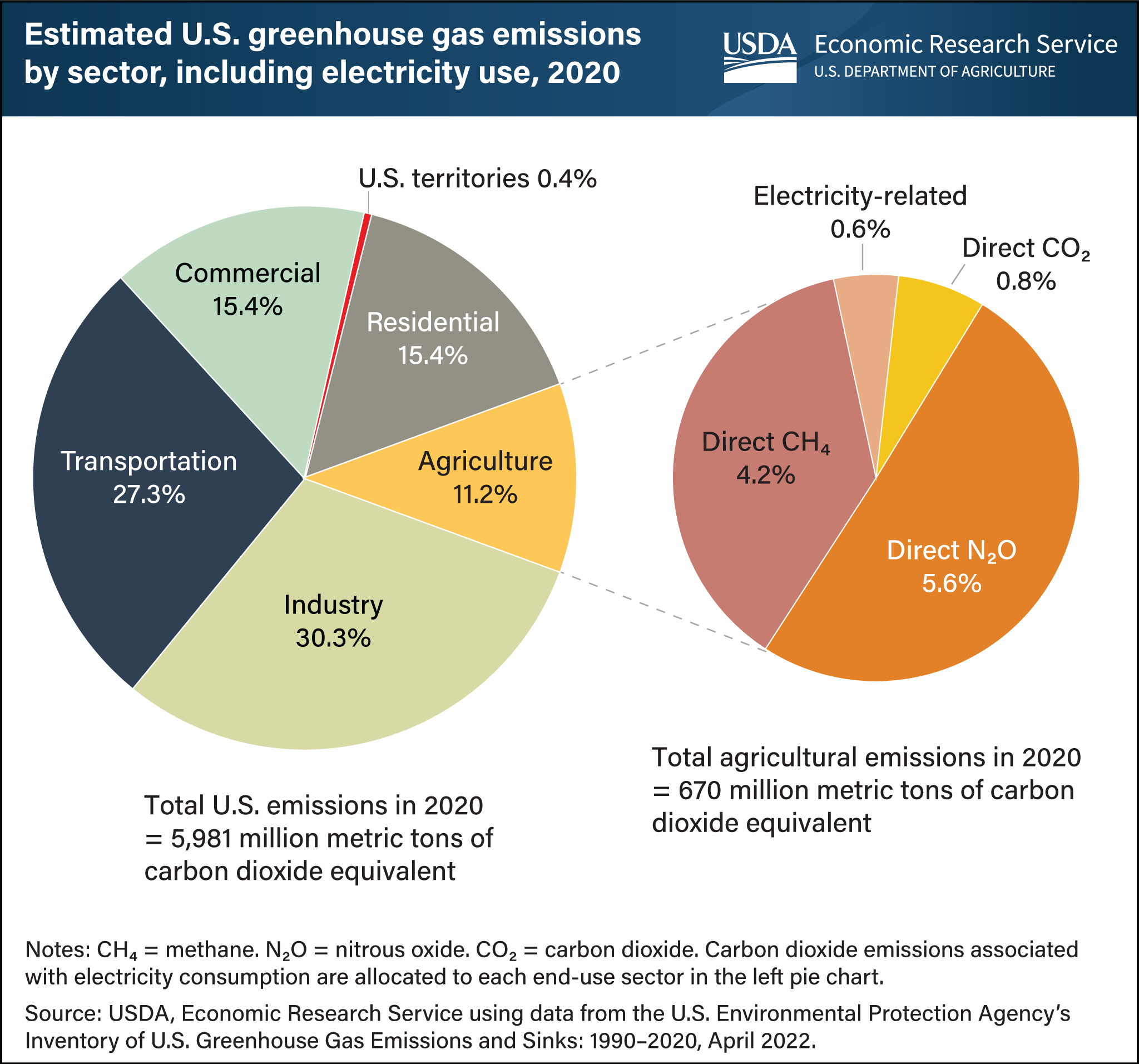

Nearly all human endeavors contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, including commercial and residential, industry, electricity, transportation, and agriculture.

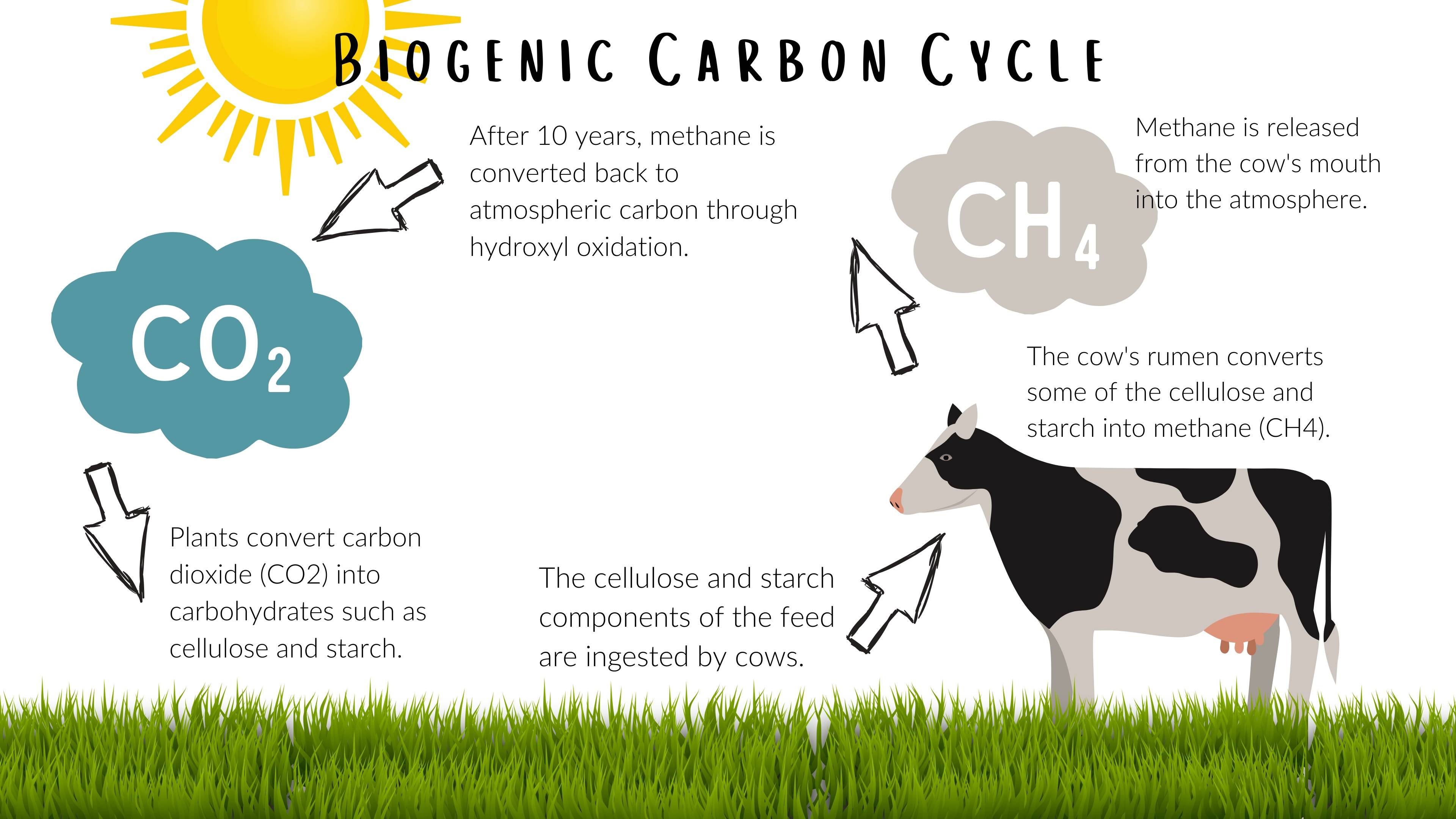

Ruminants and Methane

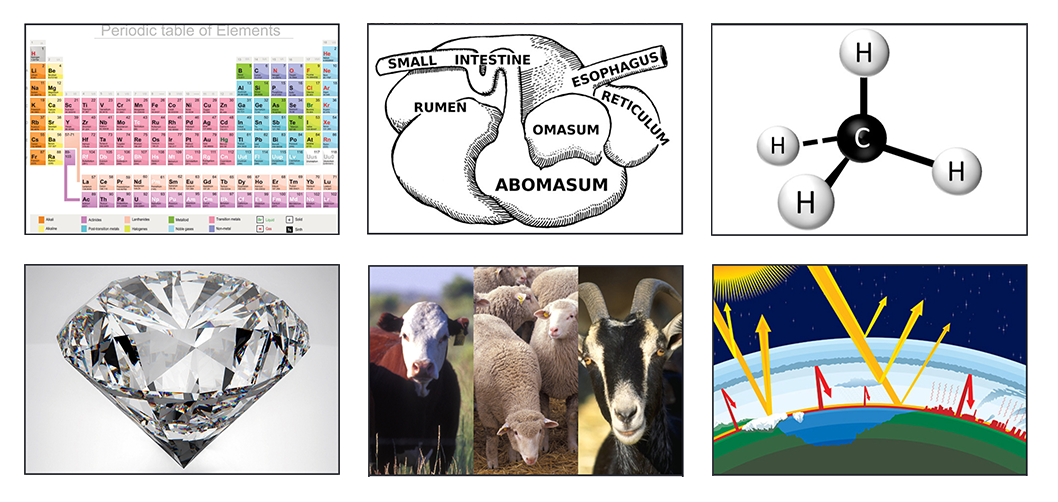

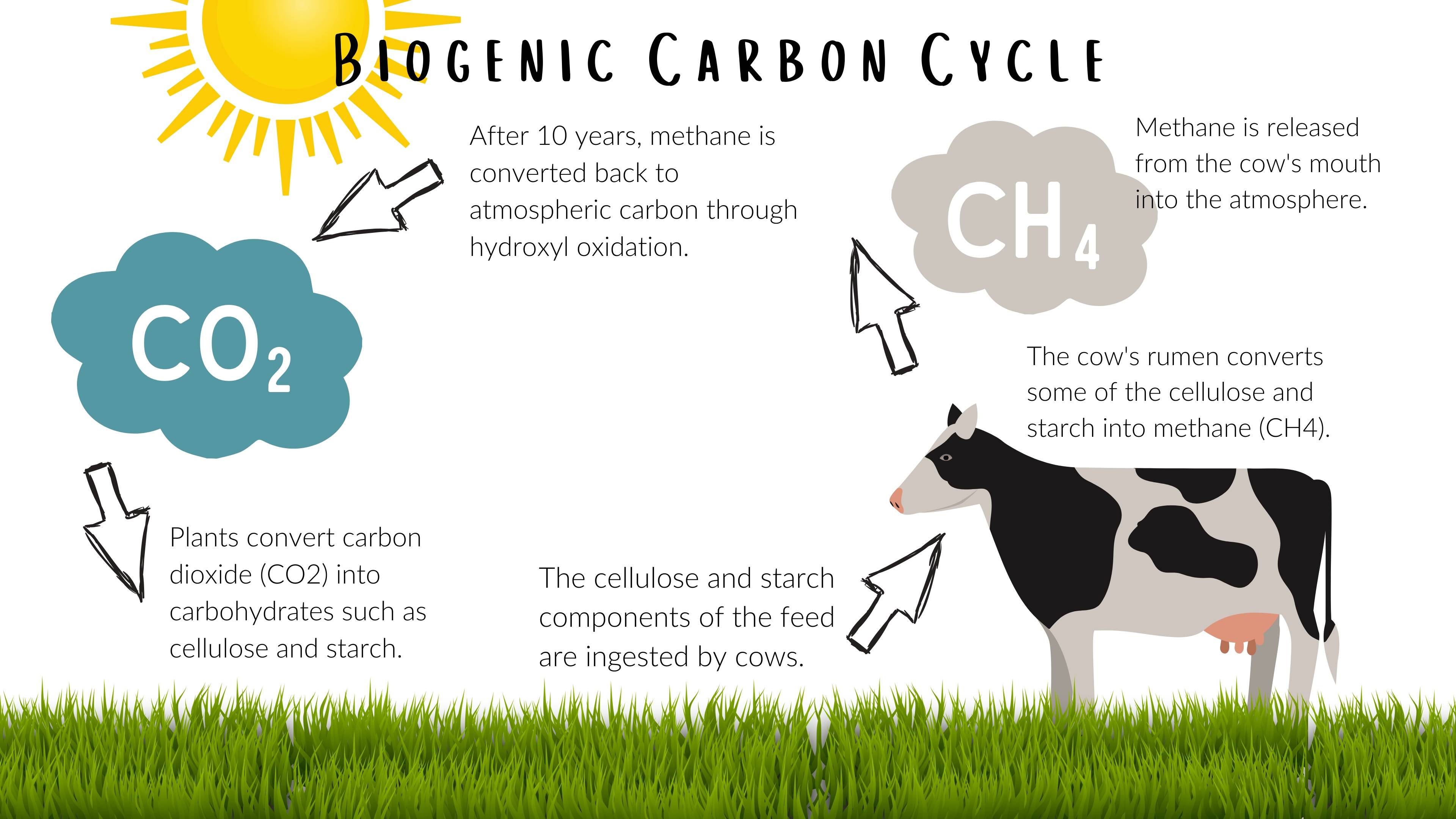

Methane (CH4) is another common greenhouse gas that is formed when a carbon atom binds with four hydrogen atoms. Methane is the second most abundant global human-caused GHG, behind carbon dioxide. Once emitted, methane has a half-life of about 10 years, while carbon dioxide has a half-life of 1,000 years.13 What many people don’t realize is that livestock-related greenhouse gases are distinctively different from fossil fuel-related gases. To understand the difference between livestock-related gases (methane) and CO2 emissions from fossil fuels, Dr. Frank Mitloehner explains the biogenic carbon cycle that occurs when cattle graze the land: Through the process of photosynthesis, plants use sunlight and water to convert CO2 into carbohydrates. When cattle ingest the grass or feed, some of the carbohydrates (cellulose and starch) are converted into methane in the cow’s rumen. The methane is then released from the cow’s mouth back into the atmosphere. After about 10 years, the methane is converted back into CO2 through hydroxyl oxidation.13 Because of this biogenic carbon cycle, if livestock herds remain constant, or cattle numbers decrease over time, then no additional carbon is being added to the atmosphere. The carbon that is emitted by our livestock is recycled carbon.13

Livestock—especially ruminants—produce methane as part of their normal digestive processes.

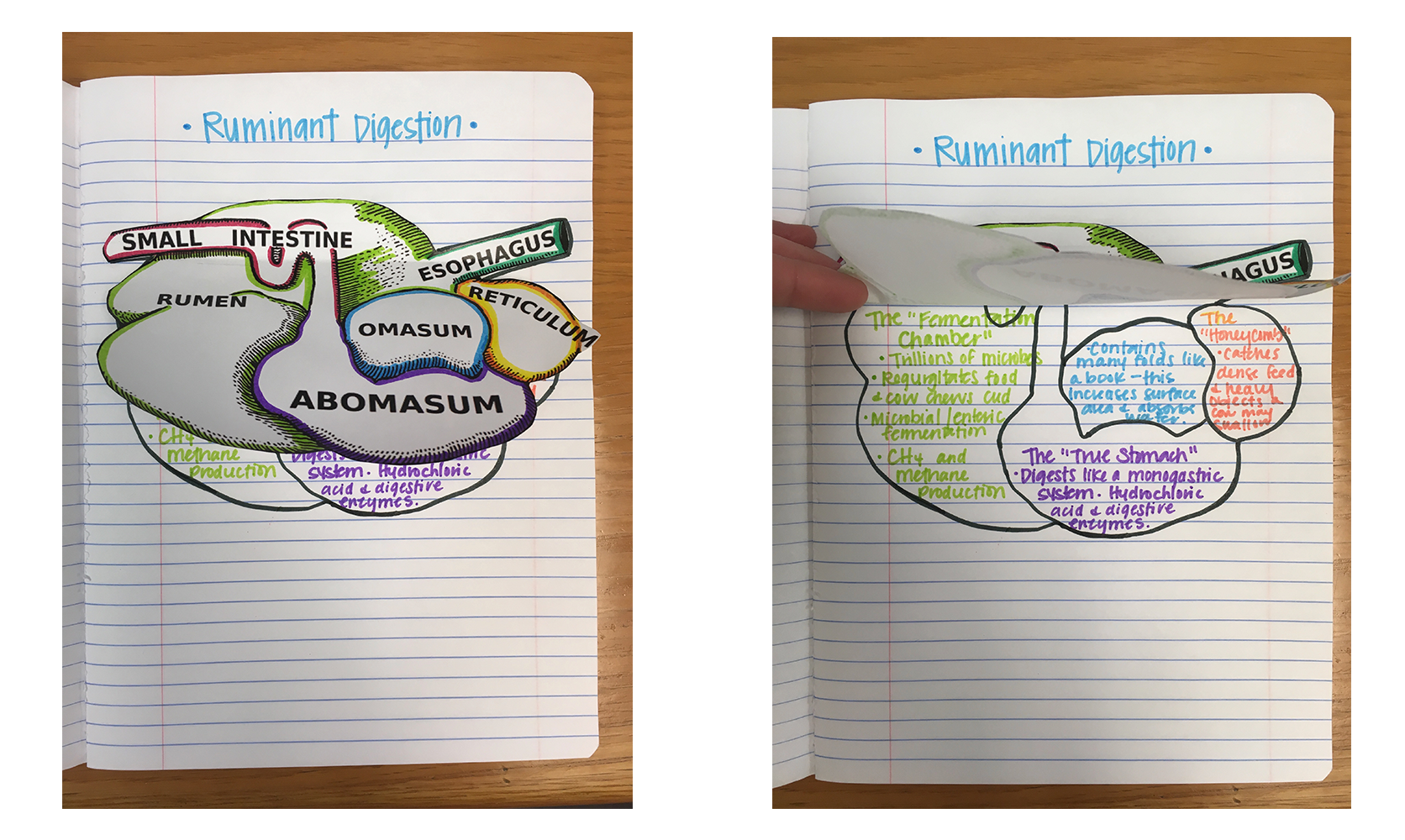

Ruminant animals have a unique digestive system that is made up of four stomach compartments: the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. During digestion, microbial fermentation occurs in the rumen and breaks down forages into material that can be absorbed and metabolized. This microbial fermentation is also known as enteric fermentation and allows ruminants to digest coarse feeds that non-ruminant animals cannot. When CH4 is produced as a byproduct from microbial fermentation, the methane is then exhaled (burped) by ruminants.

Because of their ruminant digestive system, cows have the unique ability to upcycle human-inedible forages and byproducts. Feeds like hay, grass, cottonseed meal, and distillers’ grain are upcycled into high-quality cuts of protein, iron, and zinc. Cows are not only upcycling products that humans can’t eat, but they’re also grazing in areas that are not suitable for cultivation or building.2 About two thirds of agricultural land is considered "marginal" land because it has poor soil and/or no water, so it is used to graze ruminant animals such as cattle, sheep, or goats. The remaining one third of agricultural land is arable and used for growing crops.4

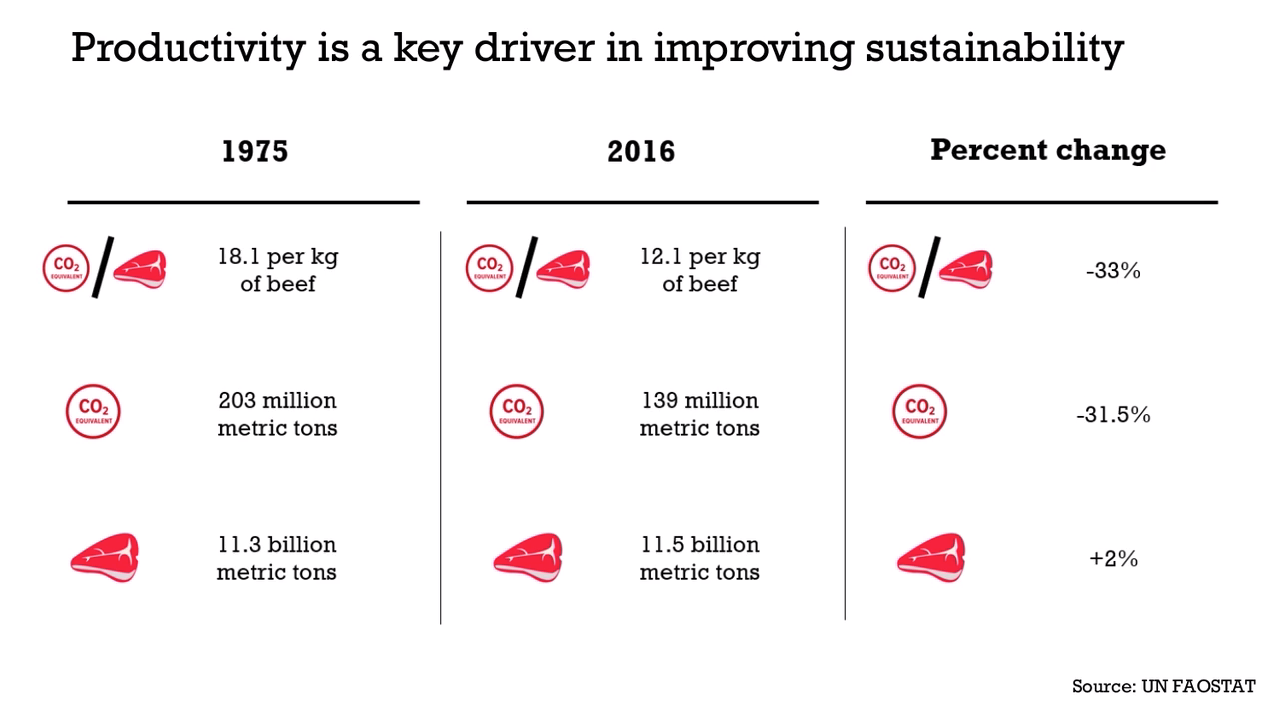

The Carbon “Hoofprint” of Beef

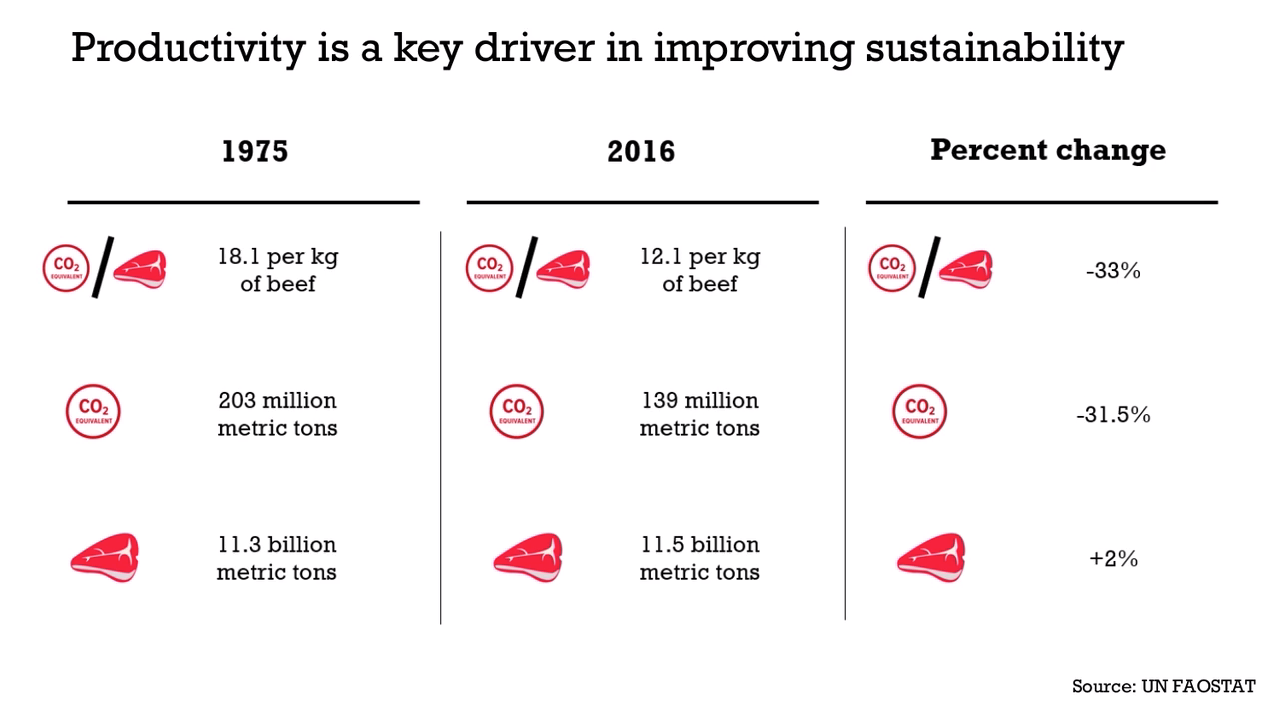

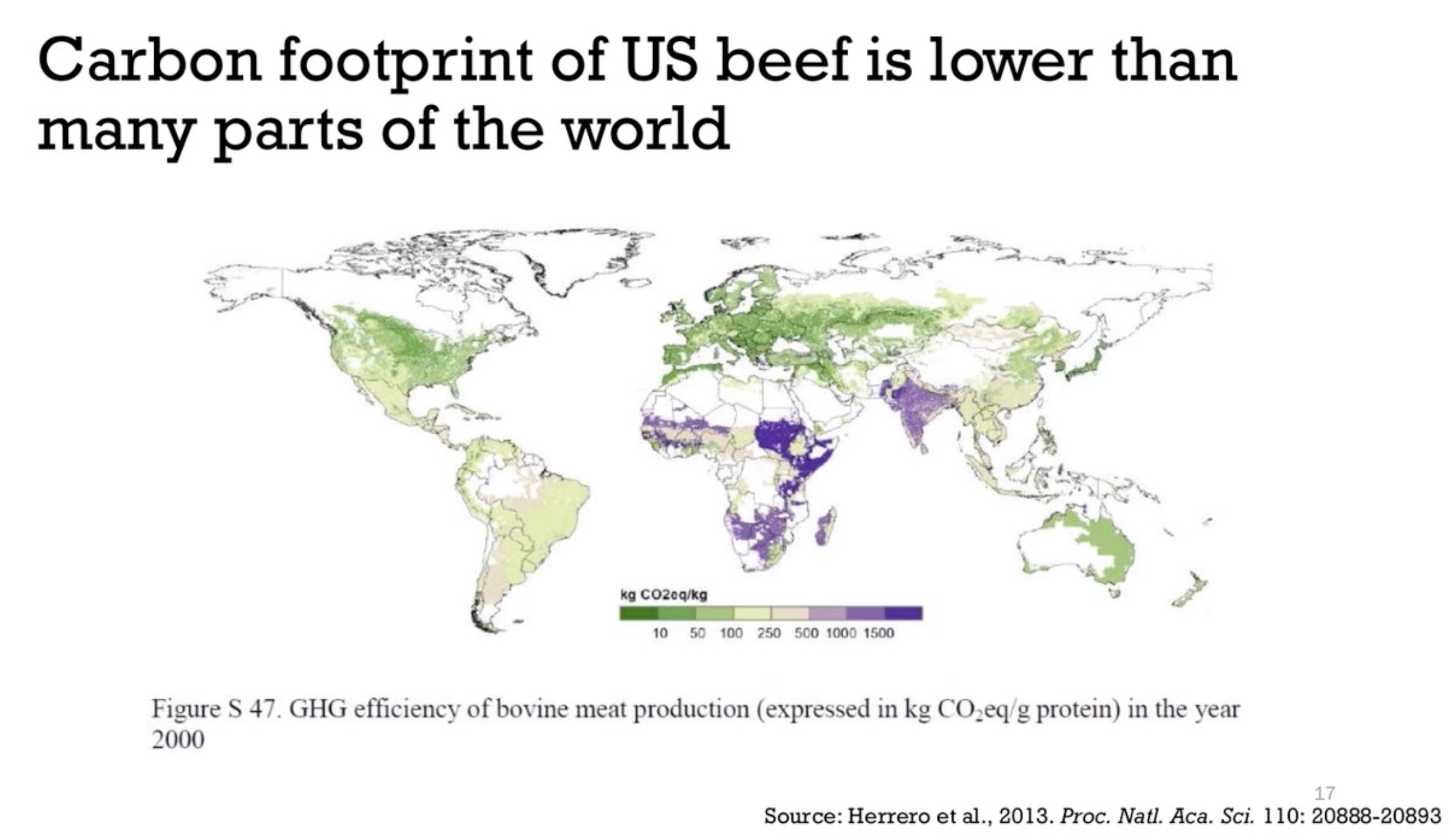

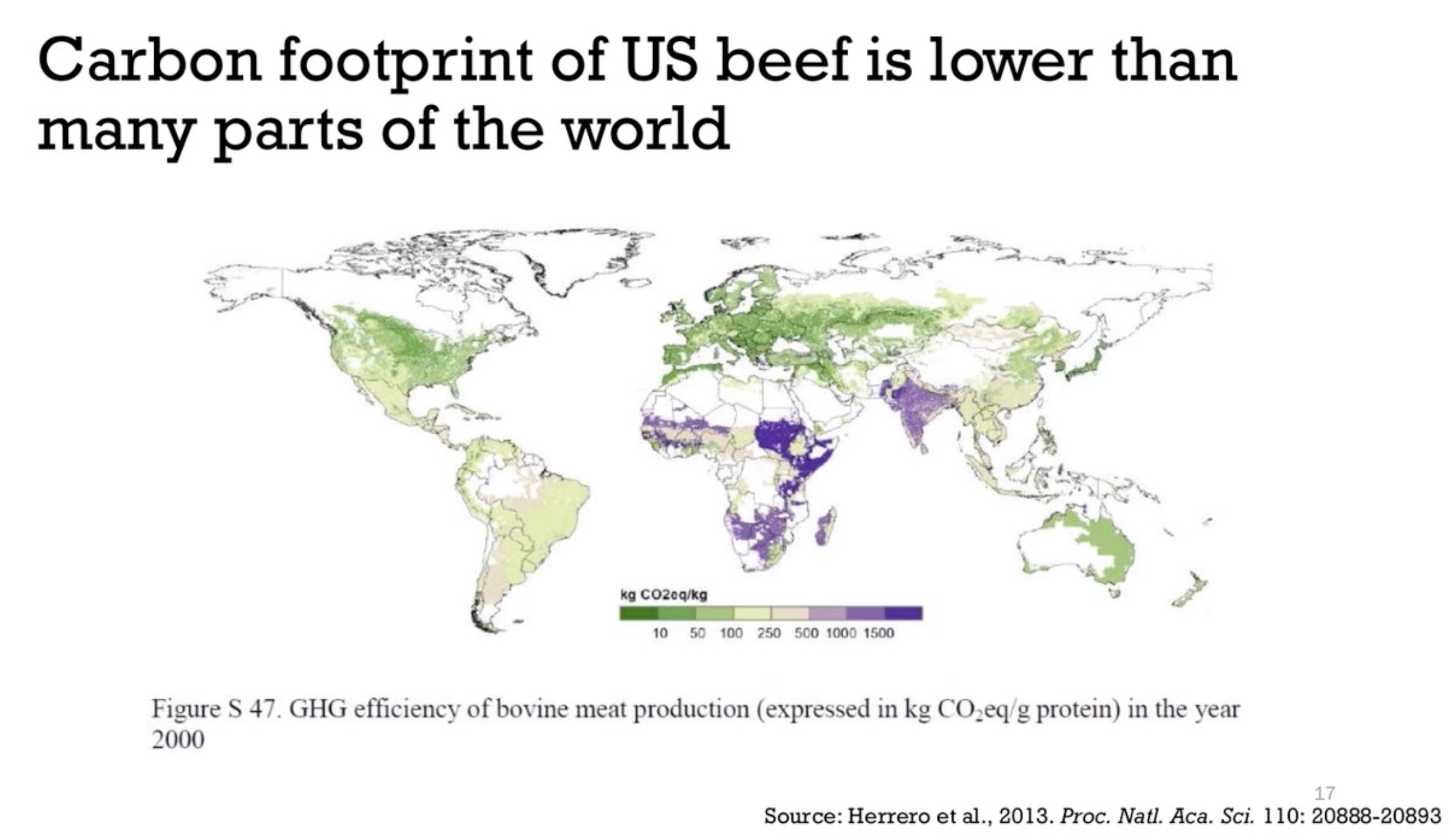

United States beef has one of the lowest carbon footprints in the world—10 to 50 times lower than some nations.6

Cows, as ruminants, produce methane. Currently, there are 32 million beef cows in the United States. Greenhouse gas emissions from cattle account for two percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.1 Methane emissions are naturally created by trillions of microbes in the rumen of cattle. One major misconception is that cows release large amounts of methane through flatulence; however, methane emissions from cattle are released when cows exhale or burp. Another common misconception is the belief that cows in feedlots produce more methane than cows eating grass or hay. Scientists have found that diets containing forages and high amounts of fiber cause the microbes in the rumen to produce more methane.4 Cattle that are fed grain produce less methane and reach market weight more quickly, thus using fewer natural resources.4

Recognizing cattle as methane contributors that accelerate climate change, some suggest changes in the diet and lifestyle of humans, such as consuming less beef or no beef at all. Assuming that all livestock in the United States disappeared and every American was vegetarian, greenhouse gas emissions would lower 2.6 percent.1 Students should think critically about the tradeoffs of beef production. Cows are methane producers who contribute to greenhouse gas emissions; however, they’re also excellent at upcycling human inedible forages—grown on marginal land not suited for cultivating crops—into high-quality cuts of meat. Will consuming less beef or eliminating beef altogether slow climate change? Is beef production the highest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions? Placing these scientific questions in context, using science, and looking at the big picture will allow students to answer these important questions.