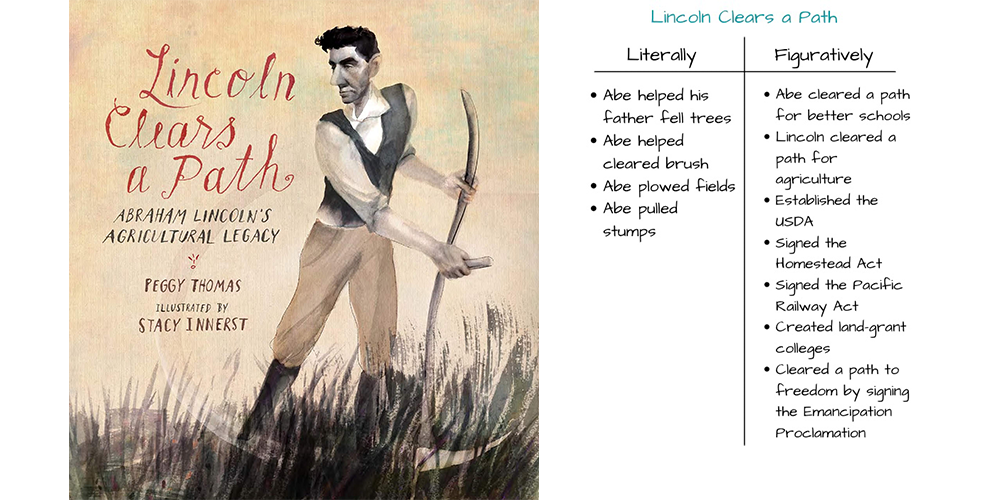

Abraham Lincoln is well known for his presidency during the Civil War, which included his fight for freedom, the passing of the Emancipation Proclamation, and his Gettysburg Address. What some might not realize, however, is his agricultural legacy.

Shortly after being elected the 16th president of the United States, the Civil War began. Abraham Lincoln quickly realized that those fighting for the Union army needed food and clothing, so Lincoln asked farmers to cultivate all of their land in order to support the military men. Because many of the men volunteered to fight in the army, wives, mothers, and sisters often times took over the farms. In 1862, there were 600,000 military men to feed and clothe. Each month during the Civil War, farmers provided 48,750 bushels of beans, 8.5 million pounds of potatoes, 24.3 million pounds of fresh beef, and over 130,000 barrels of flour.1 Lincoln recognized the hard work of the farmers feeding the army and decided the farmers needed additional support. Lincoln believed agriculture at the time was "the largest interest in the nation," and should have a proper department.1 On May 15, 1862, Abraham Lincoln established the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The USDA was created to support the farmers who were supporting the army. Support was offered to the farmers through the USDA by testing farm equipment and finding the best seeds for planting and harvesting. Today, the USDA continues to support farmers and ranchers while also promoting trade, protecting natural resources, and ensuring food safety.

In 1862, Abraham Lincoln continued his agricultural legacy by signing various acts that would impact the United States—and agriculture—for many generations. Within just a few short months, Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act, the Pacific Railway Act, and the Morrill Act.

The Homestead Act (May 20, 1862)

Anyone over the age of 17, and who did not fight against the Union, was eligible to apply to receive 160 acres of public land. If granted the acreage, settlers were required to live on the land for five years and make improvements to the land, such as building a house and planting crops. By 1934, the government processed more than 1.6 million applications.1 Although this act was critical for westward expansion, it disrupted Native American nations who lived on the land given to homesteaders.

The Pacific Railway Act (July 1, 1862)

Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act in order to fund railway construction. The Union Pacifc Railroad Company started their railway in Missouri and worked west, while the Central Pacific Railroad Company started their railway in San Francisco and headed east. The two companies connected their railroad lines in Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869. This new railroad line, that spanned from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean, allowed citizens to travel the plains in eight days and offered farmers faster transportation for products.

The Morrill Act (July 2, 1862)

A representative from Vermont, by the name of Justin Morrill, proposed that the federal government grant each state 30,000 acres to establish at least one land-grant college. Land grant-universities were designed to teach agriculture, engineering, and mechanical arts. Some states already had public universities, so in response to this act, they created new agricultural colleges rather than adding to existing universities.3 In 1890, Justin Morrill proposed a second land-grant act that ensured African Americans equal access to colleges in southern states.1

During his presidency, Abraham Lincoln accelerated agricultural research, production, and education. The USDA was able to quickly spread information to farmers about new equipment and technologies, homesteading increased the number of farms throughout the west, railways provided quick transportation of livestock and crops across states, and land-grant universities furthered agricultural education and research.