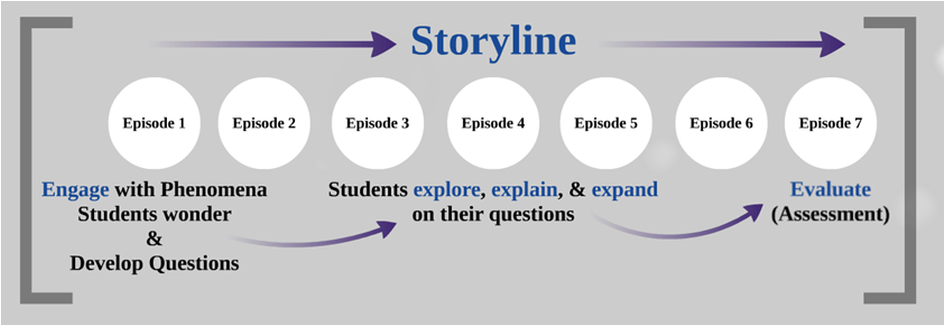

This lesson can be nested into a storyline as an episode exploring the phenomenon of photoperiodism. In this episode, students investigate the question, "Why do hens lay more eggs in the spring and summer than they do in the fall and winter?" Phenomena-based lessons include storylines which emerge based upon student questions. Other lesson plans in the National Agricultural Literacy Curriculum Matrix may be used as episodes to investigate student questions needing science-based explanations. For more information about phenomena storylines visit nextgenstorylines.org.

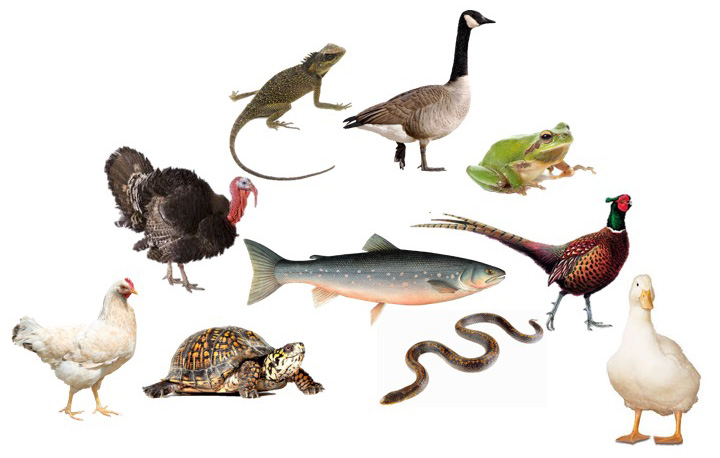

Protein is an essential nutrient in our body responsible for building tissue, cells, and muscle as well as making hormones and anti-bodies. Sources of protein include milk, yogurt, meat, beans/pulses, and eggs. One egg has around 6 grams of protein. Eggs have been consumed by humans for thousands of years. Eggs are laid by many species of birds, reptiles, and fish. However, due to the ease of raising chickens (compared to other egg-laying species) and the amount of eggs a hen can produce, eggs from chickens are most commonly consumed.

All species of chickens lay eggs. The size and color of the egg varies by the breed of the hen. Egg shell colors typically range from white to deep brown. Hens with white feathers and ear lobes lay white-shelled eggs. Hens with red feathers and ear lobes lay brown eggs. Breeds of chicken that lay white eggs are typically smaller and eat less. This makes white eggs more cost efficient to produce and typically cheaper than brown shelled eggs. There is no nutritional difference between a white- and brown-shelled egg, but some consumers still prefer one shell color over the other. For a lesson plan discussing labels and consumer choices, see Weighing in on Egg Labels, Supply, and Demand.

Hens begin laying eggs between four and six months of age depending on the breed and size of the chicken. Smaller breed hens start laying sooner than larger breed hens. Chickens do not need to be in the presence of a rooster to lay an egg. Farms raising eggs for consumption do not house roosters because there is no need to produce a fertile egg. In the wild, a hen will lay an egg per day until she has a clutch of eggs (10-15), at which time she will "set" on the eggs to begin the incubation process and hatch her eggs 21 days later. When hens are raised on farms, the eggs are collected each day. This stimulates the chicken to continue laying an egg per day.

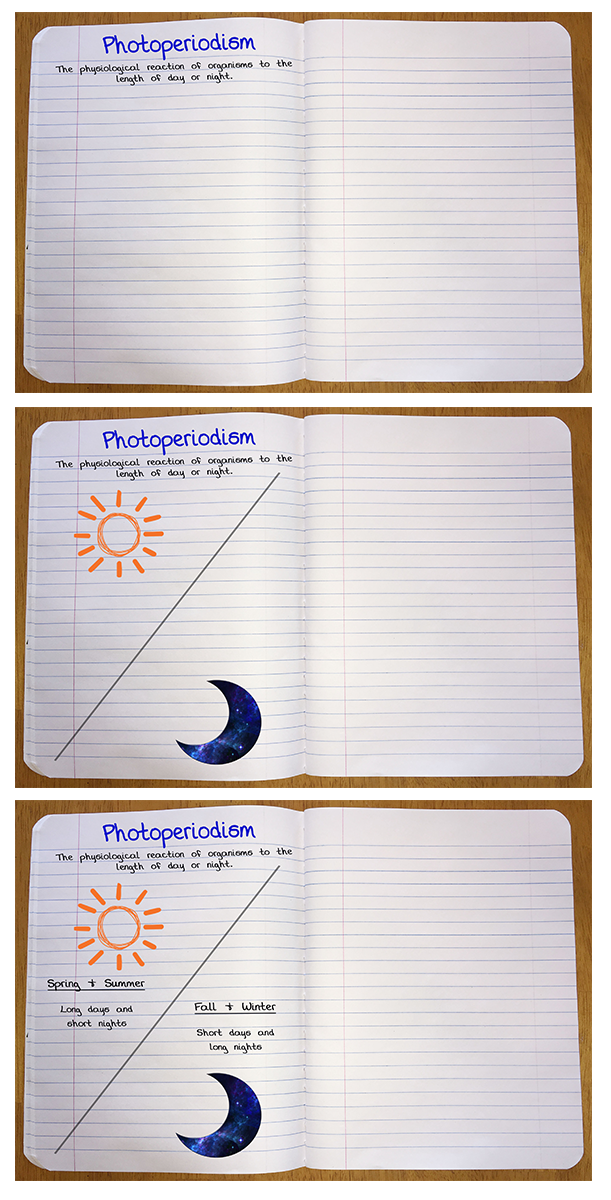

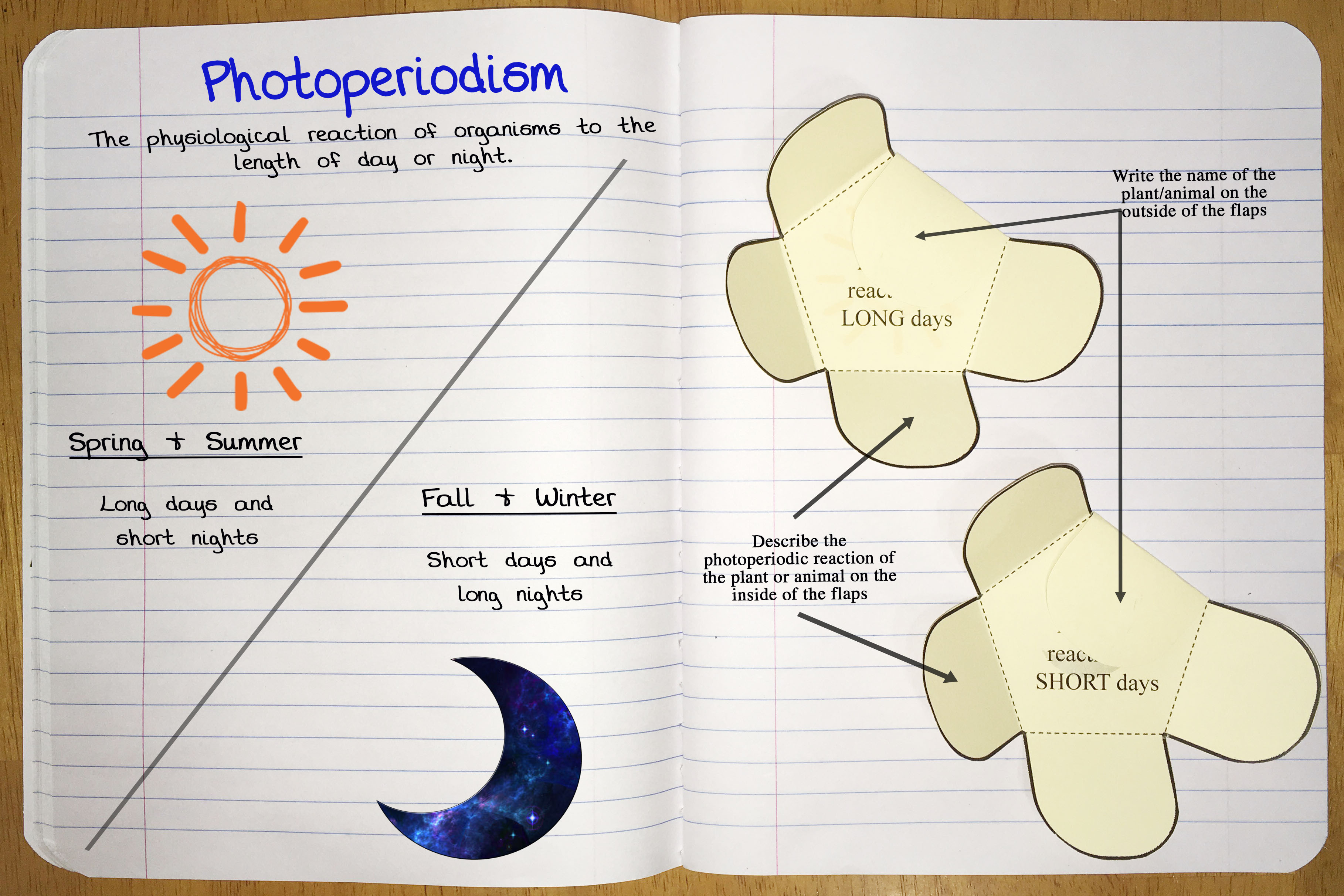

Many factors impact a hen's production of eggs including her age and body condition. Another important factor is photoperiodism which is the physiological reaction of organisms to the length of day or night. This phenomenon occurs in both plants and animals when the length of day (light) and night (darkness) triggers a specific response in the plant or animal. For example, a poinsettia plant is triggered to flower when the days are short and the nights are long. Sheep and goats begin their estrus cycle in the fall when the days get short. In contrast, horses begin their estrus cycle in the spring when the days are long. Hens are also impacted by photoperiodism. Egg production decreases and may even stop in the winter when the nights (darkness) are long and days (light) are short. Egg producers can manipulate this natural response by adding lights to their hen houses to simulate 14 hours of daylight in their environment. This artificial light will interrupt the natural molting process hens (and all birds) go through as part of a natural life cycle. The molting process is triggered by shorter days, cooler temperatures, and food scarcity. A molting hen stops egg production, loses her old feathers, and regrows new feathers. Chickens kept for commercial egg production have a different molting pattern due to a lack of seasonal environmental differences (primarily light, but also temperature) in commercial hen housing. However, just as egg farmers can simulate environmental conditions for egg production, they can also simulate conditions to induce their flock to molt by decreasing light. Molt can be induced for the entire flock simultaneously allowing hens to grow new feathers, rest from egg production, and allow their reproductive systems to rejuvenate; all leading to a longer life and more efficient egg production.4 Farmers can intentionally stagger the molt of their flocks, allowing for a steady of supply of eggs throughout the year rather than a seasonal supply.

Egg laying farms vary widely by size and production style (conventional, cage-free, free-range, etc.), but all large-scale farms use the science of photoperiodism to manage their hens' egg production.